The National Labor Relations Board enforces the National Labor Relations Act. Both are products of the Great Depression. But long before that, workers struggled in 18th and 19th Century America to improve their working conditions. There were three million members in what is now known as the labor movement when we entered World War I in 1917. President Woodrow stepped gingerly by creating a tri-partite War Labor Board in 1918. Even without enforcement powers, labor, and management agreed to refrain from strikes or lockouts because of its mediating efforts. The War Labor Board recognized the “right to organize in trade unions and to bargain collectively through chosen representatives.”[1]

The 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act outlawed “yellow-dog contracts,” pledges by workers not to join a labor union and restricted the use of court injunctions in labor disputes against strikes, picketing, and boycotts. Imposing strict procedural limitations on issuing injunctions against strike activity, the act pointed the direction toward a more even-handed relationship between the judiciary and the nation’s labor relations systems.[2]

While the right to strike is embedded in federal law, SCOTUS could, and recently has ruled in ways that could limit worker’s right to strike.[3] The NLRA has exceptions. “ A strike can’t violate a no-strike contract, and the U.S. Supreme Court has previously ruled that a “sit-down” strike, “when employees simply stay in the plant and refuse to work, thus depriving the owner of property,” is not protected by the law, nor are strikers allowed to threaten or use violence.[4]

A new poll from Gallup shows the vast majority of Americans approve of labor unions. “Gallup found that 67 percent of Americans approve of unions nationwide, in a poll conducted earlier this month. This is the fifth consecutive year that the number has surpassed the longtime average of 62 percent and is a dramatic increase since the all-time low of 48 percent approval in 2009, after the Great Recession. . . In 2022, 56 percent of Republicans approved of labor unions, and in 2023, that number dropped to 47 percent.”[5]

Politics always play a large role in labor unions and strikes. The Communications Workers of America are strident in their opposition to MAGA. “At every turn Donald Trump and his appointees have made increasing the power of corporations over working people their top priority. The list of the damage done to working people by the Trump Administration is long, and growing every day. . . Trump has encouraged freeloaders, made it more difficult to enforce collective bargaining agreements, silenced workers and restricted the freedom to join unions. Trump has packed the courts with anti-labor judges who have made the entire public sector “right to work for less” in an attempt to financially weaken unions by increasing the number of freeloaders. Trump has stacked the National Labor Relations Board with anti-union appointees who side with employers in contract disputes and support companies who delay and stall union elections, misclassify workers to take away their freedom to join a union, and silence workers. Trump has made it easier for employers to fire or penalize workers who speak up for better pay and working conditions or exercise the right to strike.”[6]

On the other side of the political aisle, Democrats support labor unions in theory, but not always in actual practice. The New York Times reported on March 10, 2023. “Modern Democratic politicians, on the other hand, have often sat out the political battle. Every Democratic president for decades, including Joe Biden, has said he favors a federal law to make it easier for workers to organize — and each of those presidents has failed to pass such a law. Democratic leaders in Congress also have not made labor law a priority. Nor have many Democratic governors.”[7]

The 2023 Writers Guild of America strike began in May 2023. CBS News reported that the SAG-AFTRA actors’ union joined the picket lines in July.[8] It was essentially a solidarity call. CNBC reported on September 20, 2023, that the Hollywood studios and writers were “near agreement to end the strike.”[9]

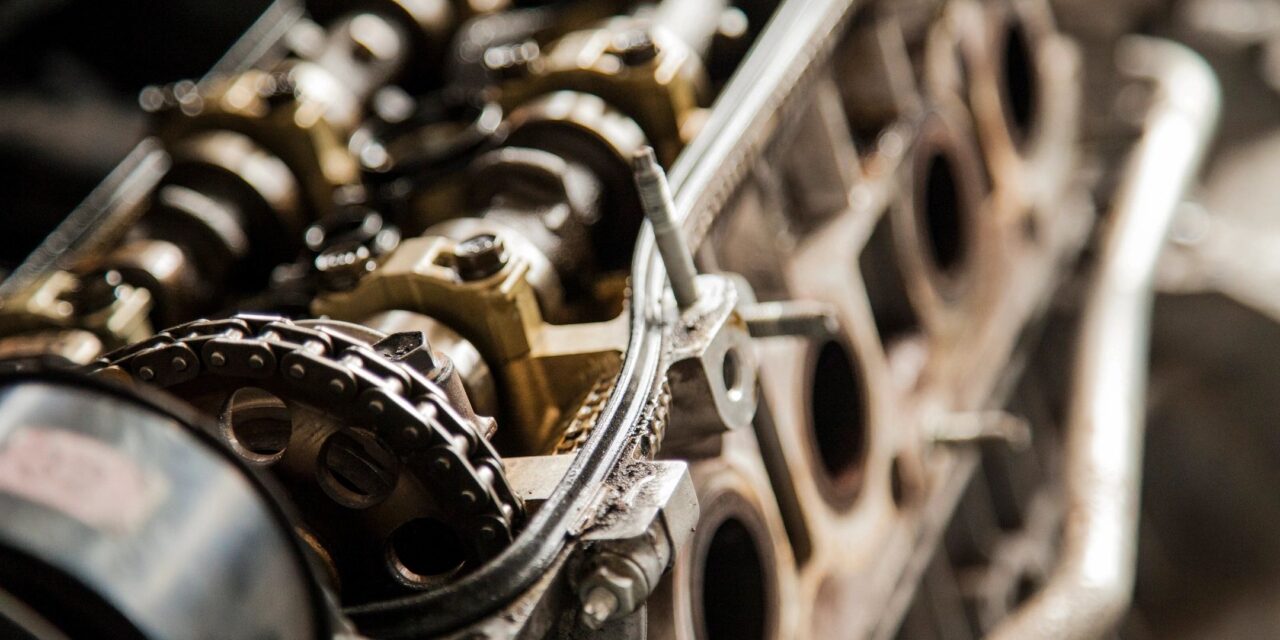

Meanwhile, Reuters reported on the expansion of the United Auto Workers strike against GM, Ford, and Chrysler parent company Stellantis.[10] This strike dwarfs the Hollywood scrum. It likely will be a long, difficult struggle that will cost everyone in the end. “The three automakers’ factories combined employ about 145,000 UAW members and produce about 50% of the vehicles manufactured annually in the US, accounting for 1.5% of US GDP. . . The hardline stance taken by the newly elected UAW president Shawn Fain contributed to the UAW’s decision to strike. In particular, he has criticized stagnant wages that do not account for inflation and has called for the end of a tiered employment system that underpays newer employees, the restoration of overtime and retirement benefits that were lost as a result of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, the institution of a four-day workweek, and improved worker protections against plant closures as electric vehicle production increases.”[11]

On the other side of the assembly line is the cost of labor relative to domestic and foreign non-union competitors, particularly as the industry transitions to electric vehicle manufacturing. The automakers will have to invest large amounts of their profits from gas cars into new production technology. Automakers claim they need to transition to building electric vehicles to meet government regulations and to remain competitive, and that this transition will require re-investing billions of dollars of their profits.[12] Ford stated that for 2023 it would lose $4.5 billion dollars in its EV business.[13]

In the autoworkers strike, unlike in the writers and actors strike, the consequences could be brutal for both sides and the country in general. The NYTimes headlined its coverage. “Strike Is A High Stakes Gamble for Autoworkers and The Labor Moment. A prolonged strike could undermine the three established U.S. automakers — General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, which owns Chrysler, Jeep, and Ram — and send the politically crucial Midwest into recession. If the union is seen as overreaching, or if it settles for a weak deal after a costly stoppage, public support could sour. . .”[14]

For almost 100 years, the right to strike has passed ethical muster. In simple terms, the moral argument for striking workers is that it would be better for society if workers had better pay and conditions. And strike action is a good tool to achieve better pay and conditions.”[15] There are philosophical approaches to workers’ rights and employers’ ethics. They are interesting but not consequential in assessing modern strikes. “Work is a subject with a long philosophical pedigree. Some of the most influential philosophical systems devote considerable attention to questions concerning who should work, how they should work, and why. For example, in the ideally just city outlined in the Republic, Plato proposed a system of labor specialization, according to which individuals are assigned to one of three economic strata, based on their inborn abilities: the laboring or mercantile class, a class of auxiliaries charged with keeping the peace and defending the city, or the ruling class of ‘philosopher-kings.’ Such a division of labor, Plato argued, will ensure that the tasks essential to the city’s flourishing will be performed by those most capable of performing them.”[16]

Actual labor cases where workers went on strike are rare in terms of ethical imperatives. All strikes are evaluated in terms of legal imperatives. But at least one modern American strike engendered ethical concerns and assessments. “In December 2005 more than 30,000 New York City transit workers walked out over economic issues despite the state of New York’s Taylor Law, which prohibits all public sector strikes. Not only did the workers face the loss of two days’ pay for each day on strike, but a court ordered that the union be fined $1 million per day. Union president Roger Toussaint held firm, likening the strikers to Rosa Parks. ‘There is a higher calling than the law,” he declared. ‘That is justice and equality.’”[17]

Rosa Parks’s protest was her refusal to get up from a bus seat she chose. She didn’t strike, she just sat. But in every sense of the word strike, her action and her refusal exemplified an ethical attempt to right a moral wrong. For her, which is also the case for many strikers in Hollywood and the mid-west, allegiance to ethical and moral obligations outweighed the law. Her story is apt to the issue of the ethicality of labor strikes.

On the chilly evening of December 1, 1955, at a bus stop on a busy street in the capital of Alabama, a 42-year-old seamstress boarded a segregated city bus to return home after a long day of work, taking a seat near the middle, just behind the front “white” section. At the next stop, more passengers got on. When every seat in the white section was taken, the bus driver ordered the black passengers in the middle row to stand so a white man could sit. The seamstress refused to give up her bus seat. Her defiance of an unfair segregation law, which required black passengers to defer to any white person who needed a seat by giving up their own, forever changed race relations in America.[18]

So, just as workers and employers engage one another in a strike over wages and the future of work in America, some attention must be given to ethical rights to be paid for what they do, and ethical rights to employers to advance corporate profits based on that labor. There should be justice and equality in labor disputes, alongside economics. When we write about strikes we are also writing about justice and equality.

[1] https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/who-we-are/our-history/pre-wagner-act-labor-relations

[2] https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/employment-law/pages/norris-laguardia-act

[3] Glacier Northwest v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters. SCOTUS docket No. 21-1449, June 1, 2023.

[4] https://www.fastcompany.com/90833266/how-the-supreme-court-could-severely-limit-workers-right-to-strike

[5] https://newrepublic.com/post/175274/gallup-poll-two-thirds-americans-support-unions

[6] https://cwa-union.org/trumps-anti-worker-record

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/10/briefing/labor-unions-democratic-party-right-to-work.html

[8] https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/striking-actors-writers-join-in-massive-hollywood-solidarity-march/

[9] https://www.cnbc.com/2023/09/21/hollywood-studios-writers-near-agreement-to-end-strike-hope-to-finalize-deal-thursday-sources-say.html

[10] https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/detroit-three-automakers-enter-final-hours-avoid-wider-uaw-strike-2023-09-22/

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_United_Auto_Workers_strike

[12] Eckert, Nora (January 25, 2022). “GM Plans Multibillion-Dollar EV Push With Michigan Plants”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

[13] Ewing, Jack (September 16, 2023). “Battle Over Electric Vehicles Is Central to Auto Strike”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 19, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023

[14] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/19/business/economy/strike-autoworkers-labor.html

[15] https://www.whattodoaboutnow.com/post/the-ethics-of-strikes

[16] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/work-labor/

[17] https://www.bostonreview.net/forum/james-gray-pope-ed-bruno-peter-kellman-right-strike/

[18] https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/stories-of-innovation/what-if/rosa-parks/

I am an author and a part-time lawyer with a focus on ethics and professional discipline. I teach creative writing and ethics to law students at Arizona State University. Read my bio.

If you have an important story you want told, you can commission me to write it for you. Learn how.

I am an author and a part-time lawyer with a focus on ethics and professional discipline. I teach creative writing and ethics to law students at Arizona State University.

I am an author and a part-time lawyer with a focus on ethics and professional discipline. I teach creative writing and ethics to law students at Arizona State University.  My latest novel is Hide & Be.

My latest novel is Hide & Be.  If you have an important story you want told, you can commission me to write it for you.

If you have an important story you want told, you can commission me to write it for you.